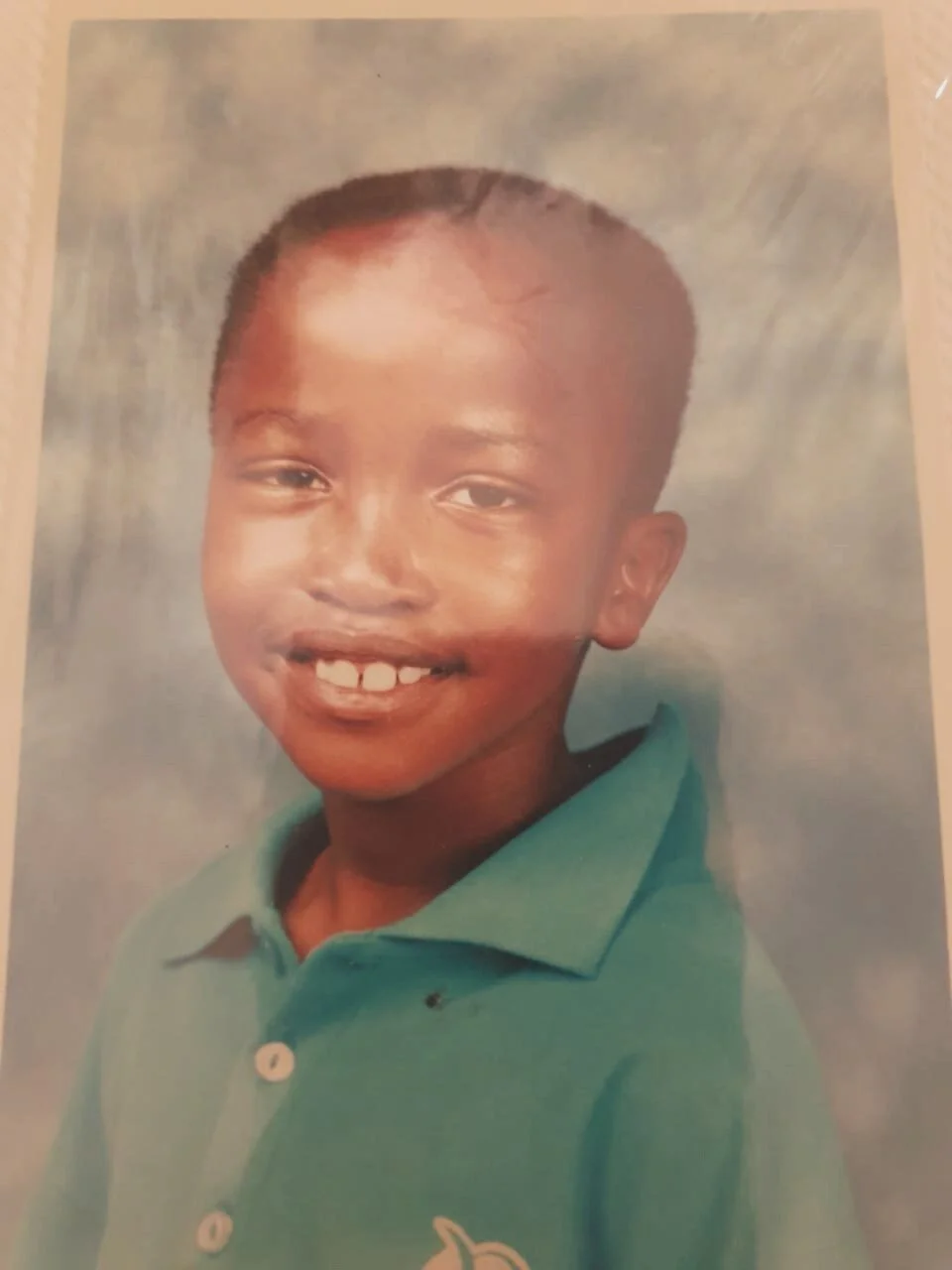

“It is very important for me as a choreographer to rewrite history and tell stories of the disenfranchised.”- Llewellyn Mnguni aka LuluBelle

Llewellyn Mnguni aka LuluBelle

Dancer / Choreographer / Performance Artist

Pronouns: They/Them

I was born and raised in the small town of Mafikeng (Mahikeng) in the North West Province. I come from a big family with a lot women, which really was an amazing energy to have for me growing up, especially being femme and all.

I know your mother was a dancer, so it goes without saying that she influenced your love and passion for performing. Would you just find yourself performing anywhere in your home?

I literally used to dance every day not really knowing what I was doing. I would knock over things and irritate my mom, I honestly think this part of my life, the passion for dance was so innocent and yet concentrated, I didn't know what to do with myself.

Can you remember any conversations you had with your mother about performance and possibly pursuing it as a career?

My mom definitely loved the fact that I wanted to dance when I was quite young, but the older I got, I think she grew more concerned as I started to take it more seriously. I remember having conversations with her constantly where she would grill me and want to know how serious I was and quite concerned about how I would take this as a career choice. I think it was a good move on her part because it made me face the future of my career and the fact that it's one of the most difficult careers in the world and can affect you negatively in a financial and psychological aspect.

“I literally used to dance every day not really knowing what I was doing. I would knock over things and irritate my mom...”

In addition to your mother’s influence, I know Backstage played quite the role in solidifying what you want to do with your life, if I’m not mistaken.

Definitely, Backstage was the first show I saw the setting of an arts establishment that catered to the teaching of different arts, and that really opened my eyes. With that I started searching for a school that I could attend and that's when I found the National School of the Arts in Johannesburg.

Right, so it’s no surprise that you ended up at the National School of Arts- what do you think that experience did for you in terms of confirming your path?

It really changed my life, this was a time where I got to grow as an artist and a queer person, I felt my most free at this school, they really advocated for self-discovery on a personal and artistic level. I have so much respect for that school and its teachers, and will forever be grateful for the positive impact it had in my life.

The world of contemporary dance was opened to you when Lorcia Cooper taught a class at the Mmabana Mmabatho Arts Centre in Mafikeng, was there a big switch in terms of how you viewed dance/choreography and its storytelling powers?

I had my first contemporary/jazz dance class with her after being a competing Latin/Ballroom dancer. It was an immediate body, mind and soul reaction to this kind of dance style, I knew then that I wanted to be a theatre performer.

Would it be accurate to say that influenced Prozac, the first piece you choreographed in Grade 11?

My influence of Prozac came from my mother taking me to a psychiatrist after I had come out to my family. I was just very interested in the game of psychology and psychiatry, especially with how through the ages society deals with mental illness. I also just started being aware of how we perpetuate this stigma of anyone that is different. My main recurring question for the dance work was- “what is normal?”.

I know you revisited Prozac in 2016. AfriPop! describes the work as “a metaphor to dissect the mental slavery of modern society especially in a South African context”. Why did you want to interrogate that?

It just felt right for me to speak about it as I was judged throughout my childhood/teenage-hood because I was different and I was not a follower of the norm-core status quo. Perception has always been an interesting topic for me and where assumptions really stem from in an individual who doesn’t even know you but feels the need to write your story according to their warped ideals and societal influence.

I just want to jump back a bit- so after NSA, you enrolled at UCT’s School of Dance. According to my research, this was the first time you were exposed to the business side of the performing arts. What’s your advice to any up-and-coming performers?

Going to University was the best decision I ever made, because I felt like I wasn't ready to be in a dance company and work immediately. I knew something was missing in terms of my knowledge and training of dance. My advice for fellow artists is to be in tune with your artistic side, but it's very important to treat your career as a business. You are the director, producer, creator. but most importantly you can learn to be the lawyer and financial manager of your empire. The penny dropped for me when I realised that representing myself and my brand in a business sense is imperative for the survival and longevity of your career, especially because we live in a world where dancers are always treated with no respect.

“The penny dropped for me when I realised that representing myself and my brand in a business sense is imperative for the survival and longevity of your career, especially because we live in a world where dancers are always treated with no respect.”

Before I delve into your work with the Dance Factory, you’ve also done a number of collaborations with local and international artists, including Umlilo aka Kwaai Diva, Canadian musician Jeremy Dutcher and photographer Zanele Muholi- what power do you think merging art forms has?

Collaborating with like-minded artists, who also represent what your essence is, helps you grow as an artist, it also invigorates the passion and creativity within you. Jeremy Dutcher and Umlilo (Kwaai Diva) are literally my favourite artists because of their raw energy and how intrinsically in tune they are with their culture and current version of themselves in their music.

Wonakess (GetUp)- Improvised Collaboration between Canadian Composer and Vocal Artist Jeremy Dutcher and South African Dancer Llewellyn Mnguni.

So, now as a principal dancer at The Dance Factory, you’ve toured the world with some incredible, subversive and groundbreaking works. I want to start with your role as Odile in Dada Masilo’s Swan Lake, which is essentially a queering of the classic ballet. How did you approach that role?

Well, at The Dance Factory we don't have a hierarchy system like a ballet company, but I do a lot of lead roles in the shows we do. Swan Lake was quite difficult as I was the only dancer en pointe, but also have scenes where I'm barefoot, and that can cause stress on your feet and other muscles. I listened to the choreographers notes and did my research for the character, but the story also resonated with me, so I also mixed in some of my own personal life experiences.

Gender roles are often so rigid and prescriptive in classical dance - why do you think it’s important to challenge those norms and create new dance vocabularies?

It is very important for me as a choreographer to rewrite history and tell stories of the disenfranchised. Contemporary dance gives me that platform because of how open it is in terms of who is lifting who, for example, as well as how bodies interact, this dance form also doesn't have a solidified structure of storytelling like ballet.

Another prominent role on your impressive resume is that of Myrtha, a sangoma, in a reworking of Giselle. What went into researching that role?

I had to research from actual sangomas and spiritual healers to first make sure it is ok to portray the role. For me, I used different spiritual characters I've always been interested in, whether it's a buddha or a monk. I remember early in my life learning about various spiritual characters that essentially have no gender, this was always so fascinating for me, so I used this as a tool to find the essence and interpretation of my role.

Llewellyn Mnguni as Myrtha in a Performance of Giselle at the National Arts Festival (2016)

How would you compare local and international audiences?

I think in our country we love the arts, but don't have a culture of watching theatre, buying art and understanding it in a context where it's literally part of our lives for escapism, healing and teaching. In Europe, it’s wildly appreciated because there is a history and tradition of art being a necessity. For us in South Africa, it also stems from colonisation and apartheid where as black people we never had the resources and now in today’s world we have this constant reality of catching up, learning, and doing our best to reclaim spaces we geographically own.

“I think in [South Africa] we love the arts, but don’t have a culture of watching theatre, buying art and understanding it in a context where it’s literally part of our lives for escapism, healing and teaching. ”

The latest piece you choreographed and performed is the Standard Bank Ovation Award-winning Resilience, “the story of an African black queer from Mafikeng. Dealing with the complexities of culture, religion and homophobia”. Why did you want to tell this story now?

I wanted to really talk about my pain, the abuse I’ve experienced from the dance industry, cis gender and queer communities, the misgender issues and toxic masculinity we have and are all experiencing in our lives every day. I wanted to highlight my optimism and forgiveness that I've carried throughout my life, which has always been my saviour. To learn and teach others how I want to be treated, essentially we are all not perfect or educated in every aspect of life, so it's really healthy to practice patience and understanding, for ourselves and for others.

And finally, what kind of legacy do you want to leave behind?

I honestly just want to be a reason for change and acceptance in society, specifically the dance and queer community. Every time there is change in society or my personal life, I feel like things are evolving and I feel drawn to having an aspect of my opinion or reality being changed because it allows for a new Llewellyn to come out of the stagnant regularity that life can easily become.